Question Number 3215 by prakash jain last updated on 07/Dec/15

$$\mathrm{Prove}\:\mathrm{that}\:\mathrm{ratio}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{circles}\:\mathrm{perimeter}\:\mathrm{to} \\ $$$$\mathrm{its}\:\mathrm{radius}\:\mathrm{is}\:\mathrm{constant}. \\ $$$$\mathrm{Proof}\:\mathrm{should}\:\mathrm{not}\:\mathrm{utilize}\:\mathrm{a}\:\mathrm{result}\:\mathrm{based} \\ $$$$\mathrm{on}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{above}\:\mathrm{fact}. \\ $$

Answered by Yozzi last updated on 07/Dec/15

![Define the curve y=(√(r^2 −x^2 )) for 0≤x≤r (r∈R). Graphically, this represents one quarter of a circle of radius r with centre (0,0). The form of this equation stems from Phythagoras′ Theorem and the definition of the locus of points creating a circle. We have (dy/dx)=((−2x×0.5)/( (√(r^2 −x^2 )))) (dy/dx)=((−x)/( (√(r^2 −x^2 ))))⇒((dy/dx))^2 =(x^2 /(r^2 −x^2 )) ∴1+((dy/dx))^2 =((r^2 −x^2 +x^2 )/(r^2 −x^2 ))=(r^2 /(r^2 −x^2 )). The differential form for arc length s of a curve y dependent on x is given by (ds/dx)=(√(1+((dy/dx))^2 )). (∗) This form also stems from Phythagoras′ Theorem. Think about a curve with a chord of length δs joining two points on a curve with vertical change δy and horizontal change δx. Then, we may form a right−angled triangle such that (δs)^2 =(δx)^2 +(δy)^2 . ∴(((δs)/(δx)))^2 =1+(((δy)/(δx)))^2 As δx→0 we obtain the differential equation ((ds/dx))^2 =1+((dy/dx))^2 . Taking (ds/dx)>0 we obtain (∗). Integrating (∗), for 0≤x≤r, leads to s=∫_0 ^r (√(1+((dy/dx))^2 ))dx s=∫_0 ^r (√(r^2 /(r^2 −x^2 )))dx s=∫_0 ^r (r/( (√(r^2 −x^2 ))))dx (r>0) s=r[sin^(−1) (x/r)]_0 ^r s=r[sin^(−1) 1−sin^(−1) 0]=rsin^(−1) 1 sin^(−1) 1 is a real constant since ∣sinx∣≤1 ∀x∈R so that sin^(−1) 1∈R. So, the entire circle perimeter P is given by P=4s=4rsin^(−1) 1. So, (P/r)=4sin^(−1) 1=constant.](https://www.tinkutara.com/question/Q3219.png)

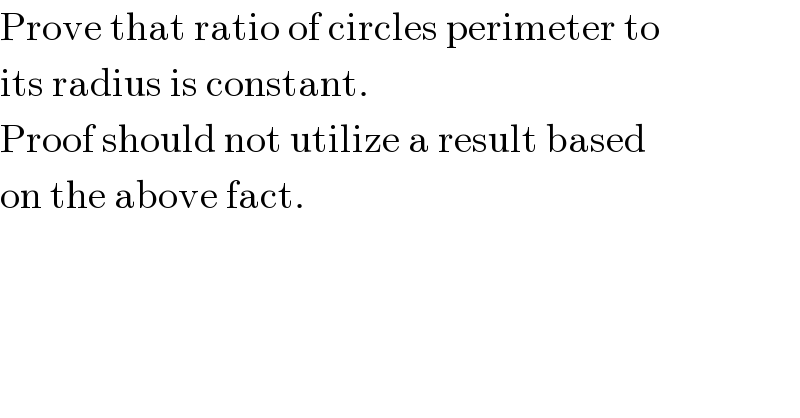

$${Define}\:{the}\:{curve}\:{y}=\sqrt{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} } \\ $$$${for}\:\mathrm{0}\leqslant{x}\leqslant\boldsymbol{{r}}\:\left(\boldsymbol{{r}}\in\mathbb{R}\right).\:{Graphically},\:{this}\: \\ $$$${represents}\:{one}\:{quarter}\:{of}\:{a}\:{circle} \\ $$$${of}\:{radius}\:\boldsymbol{{r}}\:{with}\:{centre}\:\left(\mathrm{0},\mathrm{0}\right).\:{The} \\ $$$${form}\:{of}\:{this}\:{equation}\:{stems}\:{from}\: \\ $$$${Phythagoras}'\:{Theorem}\:{and}\:{the} \\ $$$${definition}\:{of}\:{the}\:{locus}\:{of}\:{points}\:{creating} \\ $$$${a}\:{circle}.\:{We}\:{have}\:\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}=\frac{−\mathrm{2}{x}×\mathrm{0}.\mathrm{5}}{\:\sqrt{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }} \\ $$$$\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}=\frac{−{x}}{\:\sqrt{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }}\Rightarrow\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} =\frac{{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} } \\ $$$$\therefore\mathrm{1}+\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} =\frac{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} +{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }=\frac{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} }{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }. \\ $$$${The}\:{differential}\:{form}\:{for}\:{arc}\:{length}\:{s} \\ $$$${of}\:{a}\:{curve}\:{y}\:{dependent}\:{on}\:{x}\:{is}\:{given}\:{by} \\ $$$$\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\frac{{ds}}{{dx}}=\sqrt{\mathrm{1}+\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} }.\:\:\:\:\left(\ast\right) \\ $$$${This}\:{form}\:{also}\:{stems}\:{from}\: \\ $$$${Phythagoras}'\:{Theorem}.\: \\ $$$${Think}\:{about}\:{a}\:{curve}\:{with}\:{a}\:{chord} \\ $$$${of}\:{length}\:\delta{s}\:{joining}\:{two}\:{points}\:{on} \\ $$$${a}\:{curve}\:{with}\:{vertical}\:{change}\:\delta{y}\:{and} \\ $$$${horizontal}\:{change}\:\delta{x}.\:{Then},\:{we}\:{may} \\ $$$${form}\:{a}\:{right}−{angled}\:{triangle}\: \\ $$$${such}\:{that}\:\left(\delta{s}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} =\left(\delta{x}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left(\delta{y}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} . \\ $$$$\therefore\left(\frac{\delta{s}}{\delta{x}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} =\mathrm{1}+\left(\frac{\delta{y}}{\delta{x}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} \\ $$$${As}\:\delta{x}\rightarrow\mathrm{0}\:{we}\:{obtain}\:{the}\:{differential} \\ $$$${equation}\:\left(\frac{{ds}}{{dx}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} =\mathrm{1}+\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} . \\ $$$${Taking}\:\frac{{ds}}{{dx}}>\mathrm{0}\:{we}\:{obtain}\:\left(\ast\right). \\ $$$${Integrating}\:\left(\ast\right),\:{for}\:\mathrm{0}\leqslant{x}\leqslant\boldsymbol{{r}},\:{leads}\:{to}\: \\ $$$${s}=\int_{\mathrm{0}} ^{\boldsymbol{{r}}} \sqrt{\mathrm{1}+\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dx}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} }{dx} \\ $$$${s}=\int_{\mathrm{0}} ^{\boldsymbol{{r}}} \sqrt{\frac{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} }{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }}{dx} \\ $$$${s}=\int_{\mathrm{0}} ^{\boldsymbol{{r}}} \frac{\boldsymbol{{r}}}{\:\sqrt{\boldsymbol{{r}}^{\mathrm{2}} −{x}^{\mathrm{2}} }}{dx}\:\:\:\:\:\left(\boldsymbol{{r}}>\mathrm{0}\right) \\ $$$${s}=\boldsymbol{{r}}\left[{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \frac{{x}}{\boldsymbol{{r}}}\right]_{\mathrm{0}} ^{\boldsymbol{{r}}} \\ $$$${s}=\boldsymbol{{r}}\left[{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}−{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{0}\right]=\boldsymbol{{r}}{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1} \\ $$$${sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}\:{is}\:{a}\:{real}\:{constant}\:{since} \\ $$$$\mid{sinx}\mid\leqslant\mathrm{1}\:\forall{x}\in\mathbb{R}\:{so}\:{that}\:{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}\in\mathbb{R}. \\ $$$${So},\:{the}\:{entire}\:{circle}\:{perimeter}\:{P}\:{is} \\ $$$${given}\:{by}\:{P}=\mathrm{4}{s}=\mathrm{4}\boldsymbol{{r}}{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}. \\ $$$${So},\:\frac{{P}}{\boldsymbol{{r}}}=\mathrm{4}{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}={constant}. \\ $$

Commented by prakash jain last updated on 07/Dec/15

$$\mathrm{Great}. \\ $$

Commented by Rasheed Soomro last updated on 08/Dec/15

$$\mathcal{EXCEL}{lent}!\:\mathcal{A}{lso}\:{like}\:{your}\:{explanation}! \\ $$

Commented by 123456 last updated on 08/Dec/15

$$\mathrm{good}\:\mathrm{explanation} \\ $$

Answered by 123456 last updated on 08/Dec/15

![other way (???) lets l:={(x,y)∈R^2 ,x^2 +y^2 =r^2 } and take the line integral over l with f(x,y)=1 integrating f in l give the lenght P=∫_l f(x,y)dl we have that (Δl)^2 =(Δx)^2 +(Δy)^2 , taking Δx→0,Δy→0 gives dl=(√((dx)^2 +(dy)^2 )) (diferencial element of line) we can give l as x=r cos t y=r sin t 0≤t<2π note that its give the circle since x^2 +y^2 =r^2 so dl=(√((dx)^2 +(dy)^2 )) =(√((dt)^2 [((dx/dt))^2 +((dy/dt))^2 ])) =(√(((dx/dt))^2 +((dy/dt))^2 ))dt so P=∫_0 ^(2π) (√(((d/dt)rcos t)^2 +((d/dt)rsin t)^2 ))dt =r∫_0 ^(2π) (√(sin^2 t+cos^2 t))dt =r∫_0 ^(2π) dt =2πr (P/r)=2π=const (multivariable calculus version of above proof)](https://www.tinkutara.com/question/Q3229.png)

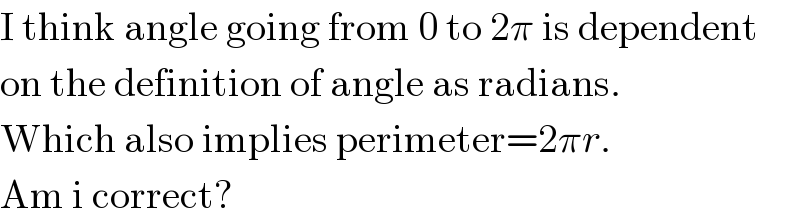

$$\mathrm{other}\:\mathrm{way}\:\left(???\right) \\ $$$$\mathrm{lets}\:{l}:=\left\{\left({x},{y}\right)\in\mathbb{R}^{\mathrm{2}} ,{x}^{\mathrm{2}} +{y}^{\mathrm{2}} ={r}^{\mathrm{2}} \right\} \\ $$$$\mathrm{and}\:\mathrm{take}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{line}\:\mathrm{integral}\:\mathrm{over}\:{l}\:\mathrm{with} \\ $$$${f}\left({x},{y}\right)=\mathrm{1} \\ $$$$\mathrm{integrating}\:{f}\:\mathrm{in}\:{l}\:\mathrm{give}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{lenght} \\ $$$$\mathrm{P}=\underset{{l}} {\int}{f}\left({x},{y}\right){dl} \\ $$$$\mathrm{we}\:\mathrm{have}\:\mathrm{that}\:\left(\Delta{l}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} =\left(\Delta{x}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left(\Delta{y}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} ,\:\mathrm{taking} \\ $$$$\Delta{x}\rightarrow\mathrm{0},\Delta{y}\rightarrow\mathrm{0}\:\mathrm{gives} \\ $$$${dl}=\sqrt{\left({dx}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left({dy}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} }\:\left(\mathrm{diferencial}\:\mathrm{element}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{line}\right) \\ $$$$\mathrm{we}\:\mathrm{can}\:\mathrm{give}\:{l}\:\mathrm{as} \\ $$$${x}={r}\:\mathrm{cos}\:{t} \\ $$$${y}={r}\:\mathrm{sin}\:{t} \\ $$$$\mathrm{0}\leqslant{t}<\mathrm{2}\pi \\ $$$$\mathrm{note}\:\mathrm{that}\:\mathrm{its}\:\mathrm{give}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{circle}\:\mathrm{since} \\ $$$${x}^{\mathrm{2}} +{y}^{\mathrm{2}} ={r}^{\mathrm{2}} \\ $$$$\mathrm{so} \\ $$$${dl}=\sqrt{\left({dx}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left({dy}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} } \\ $$$$=\sqrt{\left({dt}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} \left[\left(\frac{{dx}}{{dt}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dt}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} \right]} \\ $$$$=\sqrt{\left(\frac{{dx}}{{dt}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left(\frac{{dy}}{{dt}}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} }{dt} \\ $$$$\mathrm{so} \\ $$$$\mathrm{P}=\underset{\mathrm{0}} {\overset{\mathrm{2}\pi} {\int}}\sqrt{\left(\frac{{d}}{{dt}}{r}\mathrm{cos}\:{t}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} +\left(\frac{{d}}{{dt}}{r}\mathrm{sin}\:{t}\right)^{\mathrm{2}} }{dt} \\ $$$$={r}\underset{\mathrm{0}} {\overset{\mathrm{2}\pi} {\int}}\sqrt{\mathrm{sin}^{\mathrm{2}} {t}+\mathrm{cos}^{\mathrm{2}} {t}}{dt} \\ $$$$={r}\underset{\mathrm{0}} {\overset{\mathrm{2}\pi} {\int}}{dt} \\ $$$$=\mathrm{2}\pi{r} \\ $$$$\frac{\mathrm{P}}{{r}}=\mathrm{2}\pi=\mathrm{const} \\ $$$$\left(\mathrm{multivariable}\:\mathrm{calculus}\:\mathrm{version}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{above}\right. \\ $$$$\left.\mathrm{proof}\right) \\ $$

Commented by prakash jain last updated on 08/Dec/15

$$\mathrm{I}\:\mathrm{think}\:\mathrm{angle}\:\mathrm{going}\:\mathrm{from}\:\mathrm{0}\:\mathrm{to}\:\mathrm{2}\pi\:\mathrm{is}\:\mathrm{dependent} \\ $$$$\mathrm{on}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{definition}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{angle}\:\mathrm{as}\:\mathrm{radians}. \\ $$$$\mathrm{Which}\:\mathrm{also}\:\mathrm{implies}\:\mathrm{perimeter}=\mathrm{2}\pi{r}. \\ $$$$\mathrm{Am}\:\mathrm{i}\:\mathrm{correct}? \\ $$

Commented by 123456 last updated on 08/Dec/15

$$\mathrm{hehehe},\:\mathrm{you}\:\mathrm{got}\:\mathrm{me}. \\ $$$$\mathrm{s}\:\mathrm{is}\:\mathrm{lenght}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{arc}\:\mathrm{sector} \\ $$$$\mathrm{radians}\:\rightarrow\:\theta=\frac{{s}}{{r}} \\ $$$$\mathrm{degree}\:\rightarrow\:\mathrm{1}°=\frac{\mathrm{1}}{\mathrm{360}}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{a}\:\mathrm{circle} \\ $$$$\mathrm{grade}\:\rightarrow\:\mathrm{1}\:\mathrm{gon}=\frac{\mathrm{1}}{\mathrm{400}}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{a}\:\mathrm{circle} \\ $$$$\mathrm{2}\pi=\mathrm{360}°=\mathrm{400}\:\mathrm{gon} \\ $$

Commented by Yozzi last updated on 08/Dec/15

$${That}\:{is}\:{why}\:{I}\:{hadn}'{t}\:{evalauted}\:{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1} \\ $$$${in}\:{my}\:{proof}.\:\pi/\mathrm{2}\:{would}\:{have}\:{appeared} \\ $$$${and}\:{I}\:{think}\:\pi\:{traditionally}\:{stems}\: \\ $$$${from}\:{the}\:{definition}\:{of}\:{circumference} \\ $$$${as}\:{stating}\:{that}\:{the}\:{ratio}\:{between}\:{the} \\ $$$${circumference}\:{and}\:{diameter}\:{of}\:{a} \\ $$$${circle}\:{is}\:{a}\:{constant}\:{denoted}\:{by}\:\pi. \\ $$$${I}\:{thought}\:{that}\:{I}\:{needed}\:{to}\:{explain} \\ $$$${the}\:{origin}\:{of}\:{every}\:{result}\:{I}\:{used}. \\ $$

Commented by prakash jain last updated on 08/Dec/15

$$\mathrm{Once}\:\mathrm{you}\:\mathrm{got}\:\mathrm{to}\:\mathrm{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}.\:\mathrm{The}\:\mathrm{proof}\:\mathrm{of}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{fact} \\ $$$$\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{ratio}\:\mathrm{is}\:\mathrm{constant}\:\mathrm{is}\:\mathrm{complete}.\:\mathrm{Evaluating}\:\mathrm{sin}^{−\mathrm{1}} \mathrm{1}\: \\ $$$$\mathrm{after}\:\mathrm{that}\:\mathrm{point}\:\mathrm{keeps}\:\mathrm{the}\:\mathrm{proof}\:\mathrm{still}\:\mathrm{valid}. \\ $$