Question and Answers Forum

Question Number 7249 by Rasheed Soomro last updated on 19/Aug/16

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 19/Aug/16

Commented by Rasheed Soomro last updated on 19/Aug/16

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 19/Aug/16

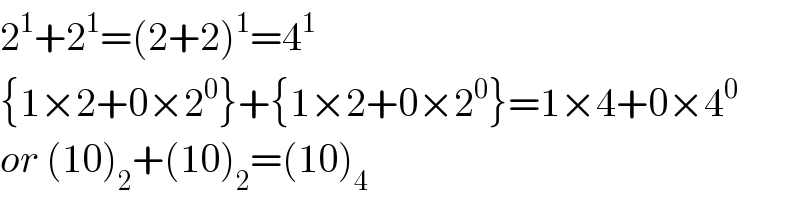

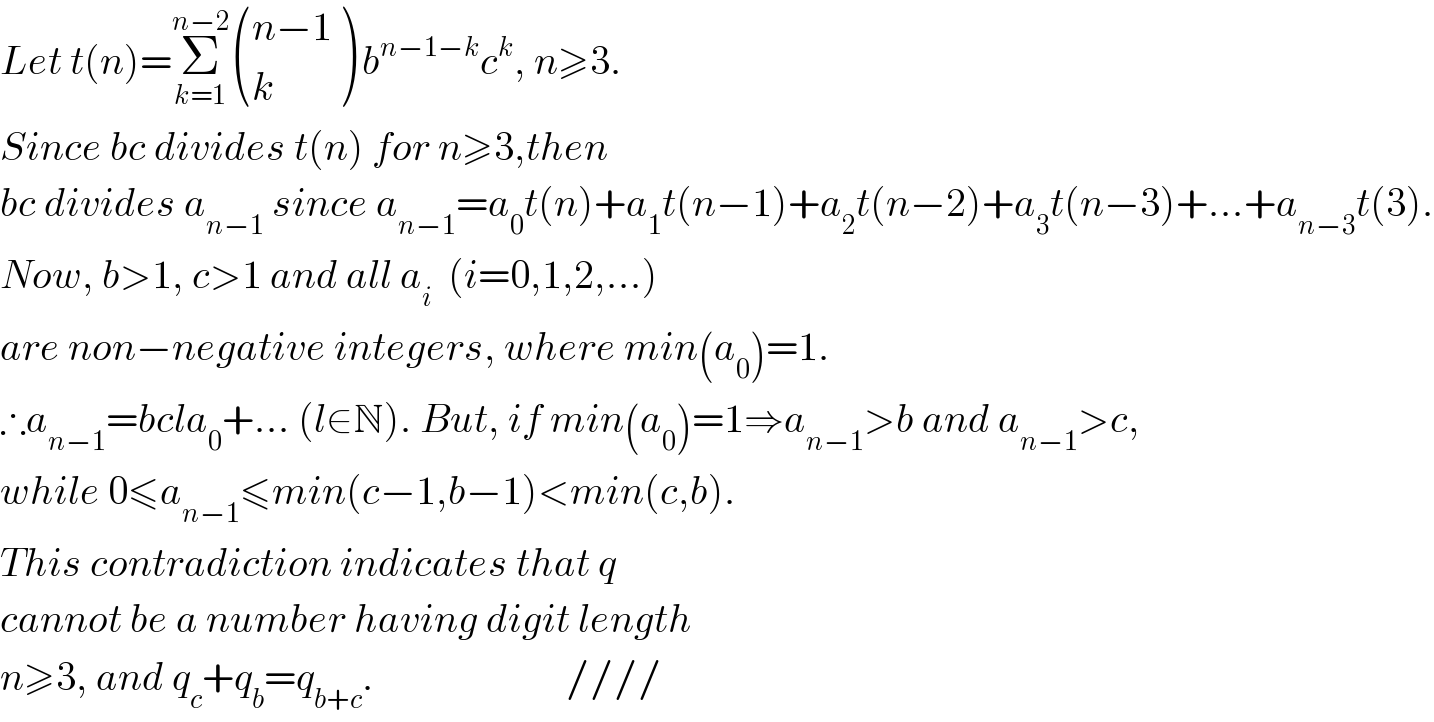

![wxyz_a +wxyz_b =wxyz_(a+b) (∗) Suppose wxyz is an integer identical on both sides of (∗) e.g 1234_a +1234_b =1234_(a+b) for some given a,b∈N. [wa^3 +xa^2 +ya+z]+[wb^3 +xb^2 +yb+z]=w(a+b)^3 +x(a+b)^2 +y(a+b)+z w{a^3 +b^3 −(a+b)^3 }+x{a^2 +b^2 −(a+b)^2 }+y(a+b−a−b)+2z−z=0 w{−3a^2 b−3ab^2 }+x{−2ab}+z=0 w{3a^2 b+3ab^2 }+2xab−z=0 The form of the above equation is independent of the value of y∈N. z=ab(2x+3w(a+b)) w,x∈Z^≥ , a,b∈N−{1} and ab∣z. If x>0 or w>0 then 2x+3w(a+b)>1⇒z>ab>a and z>b. However, 0≤z≤min(a−1,b−1)<min(a,b) for z in wxyz_a and wxyz_b , a contradiction. Hence, we must have x=w=0 ⇒ z=0. ∴ we get 00y0_a +00y0_b =00y0_(a+b) or y0_a +y0_b =y0_(a+b) or ya+yb=y(a+b) for any y∈N ,0≤y<a,y<b when a and b are known bases. No four digit integer wxyz satisfies wxyz_a +wxyz_b =wxyz_(a+b) .](Q7257.png)

Commented by Rasheed Soomro last updated on 20/Aug/16

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 20/Aug/16

Commented by Rasheed Soomro last updated on 20/Aug/16

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 20/Aug/16

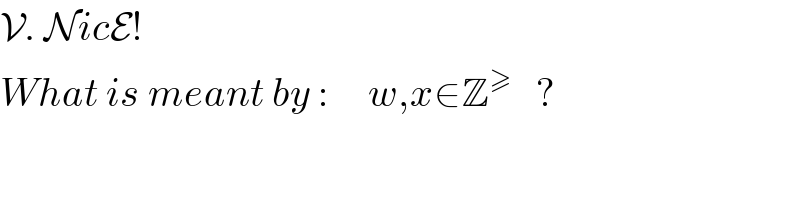

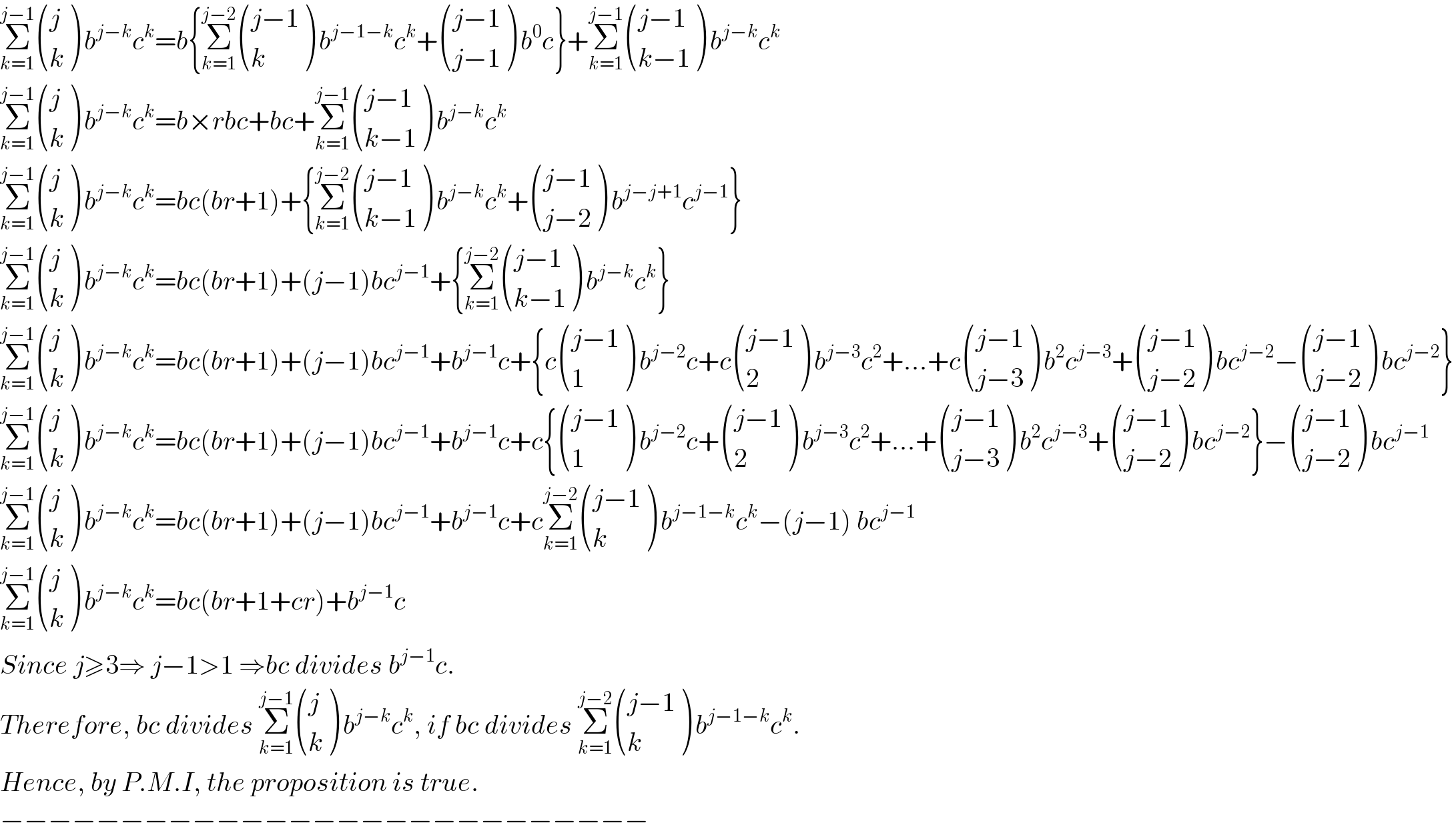

![Let q be a number of digit length n≥3, and c,b∈[N−{1}]. Write k_m for the number k corresponding to base m≥2. Suppose that q_c +q_b =q_(c+b) . Then, no q exists satisfying this equation for n≥3. −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−− PROOF: Looking at the equation q_c +q_b =q_(c+b) , q has a digit representation of the form q=a_0 ^� a_1 ^� a_2 ^� a_3 ^� ...a_(n−1) ^� where 0≤a_i ≤min(c−1,b−1) for i=1 , 2 , ... , n−1, and 1≤a_0 ≤min(c−1,b−1). Therefore q_c =Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) a_i c^(n−1−i) , q_b =Σ_(i=1) ^(n−1) a_i b^(n−1−i) and q_(c+b) =Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) a_i (b+c)^(n−1−i) . Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) a_i c^(n−1−i) +Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) a_i b^(n−1−i) =Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) a_i (b+c)^(n−1−i) Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) {a_i c^(n−1−i) +a_i b^(n−1−i) −a_i (b+c)^(n−1−i) }=0 Σ_(i=0) ^(n−1) [a_i {c^(n−1−i) +b^(n−1−i) −(b+c)^(n−1−i) }]=0 Σ_(i=0) ^(n−3) [a_i {c^(n−1−i) +b^(n−1−i) −(b+c)^(n−1−i) }]+a_(n−2) {c^(n−1−n+2) +b^(n−1−n+2) −(b+c)^(n−1−n+2) }+a_(n−1) {c^(n−1−n+1) +b^(n−1−n+1) −(b+c)^(n−1−n+1) }=0 Σ_(i=0) ^(n−3) [a_i {c^(n−1−i) +b^(n−1−i) −(b+c)^(n−1−i) }]+a_(n−2) {c+b−(b+c)}+a_(n−1) {1+1−1}=0 Σ_(i=0) ^(n−3) [a_i {c^(n−1−i) +b^(n−1−i) −(b+c)^(n−1−i) }]+a_(n−1) =0 a_(n−1) =Σ_(i=0) ^(n−3) [a_i {(b+c)^(n−1−i) −c^(n−1−i) −b^(n−1−i) }] According to the Binomial Theorem, (b+c)^(n−1−i) =Σ_(k=0) ^(n−1−i) (((n−1−i)),(k) ) b^(n−1−i−k) c^k or (b+c)^(n−1−i) =b^(n−1−i) +c^(n−1−i) +Σ_(k=1) ^(n−2−i) (((n−1−i)),(k) ) b^(n−1−i−k) c^k . ∴ (b+c)^(n−1−i) −b^(n−1−i) −c^(n−1−i) =Σ_(k=1) ^(n−2−i) (((n−1−i)),(k) ) b^(n−1−i−k) c^k . a_(n−1) =Σ_(i=0) ^(n−3) [a_i {Σ_(k=1) ^(n−2−i) (((n−1−i)),(k) ) b^(n−1−i−k) c^k }] a_(n−1) =a_0 {Σ_(k=1) ^(n−2) (((n−1)),(k) ) b^(n−1−k) c^k }+a_1 {Σ_(k=1) ^(n−3) (((n−2)),(k) ) b^(n−2−k) c^k } +a_2 {Σ_(k=1) ^(n−4) (((n−3)),(k) ) b^(n−3−k) c^k }+...+a_(n−4) {Σ_(k=1) ^2 ((3),(k) ) b^(3−k) c^k }+a_(n−3) {Σ_(k=1) ^1 ((2),(k) ) b^(2−k) c^k } Observe that the form of the above equation is indepedent of a_(n−2) ; so a_(n−2) is a free variable such that 0≤a_(n−2) ≤min(c−1,b−1). −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−− Proposition: For any n≥3, bc divides Σ_(k=1) ^(n−2) (((n−1)),(k) ) b^(n−1−k) c^k . Proof (induction): Base case n=3: Σ_(k=1) ^(3−2) (((3−1)),(k) ) b^(3−1−k) c^k = ((2),(1) ) bc ⇒bc divides Σ_(k=1) ^(n−2) (((n−1)),(k) ) b^(n−1−k) c^k for n=3. Inductive step: Suppose bc divides Σ_(k=1) ^(j−2) (((j−1)),(k) ) b^(j−1−k) c^k for n=j. i.e Σ_(k=1) ^(j−2) (((j−1)),(k) ) b^(j−1−k) c^k =rbc for some r∈N. For n=j+1, we have that Σ_(k=1) ^(j−1) ((j),(k) ) b^(j−k) c^k =Σ_(k=1) ^(j−1) { (((j−1)),(k) ) + (((j−1)),((k−1)) )}b^(j−k) c^k](Q7277.png)

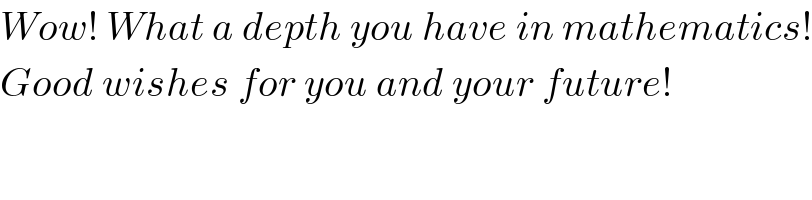

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 20/Aug/16

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 20/Aug/16

Commented by Rasheed Soomro last updated on 20/Aug/16

Commented by Yozzia last updated on 20/Aug/16